Munich

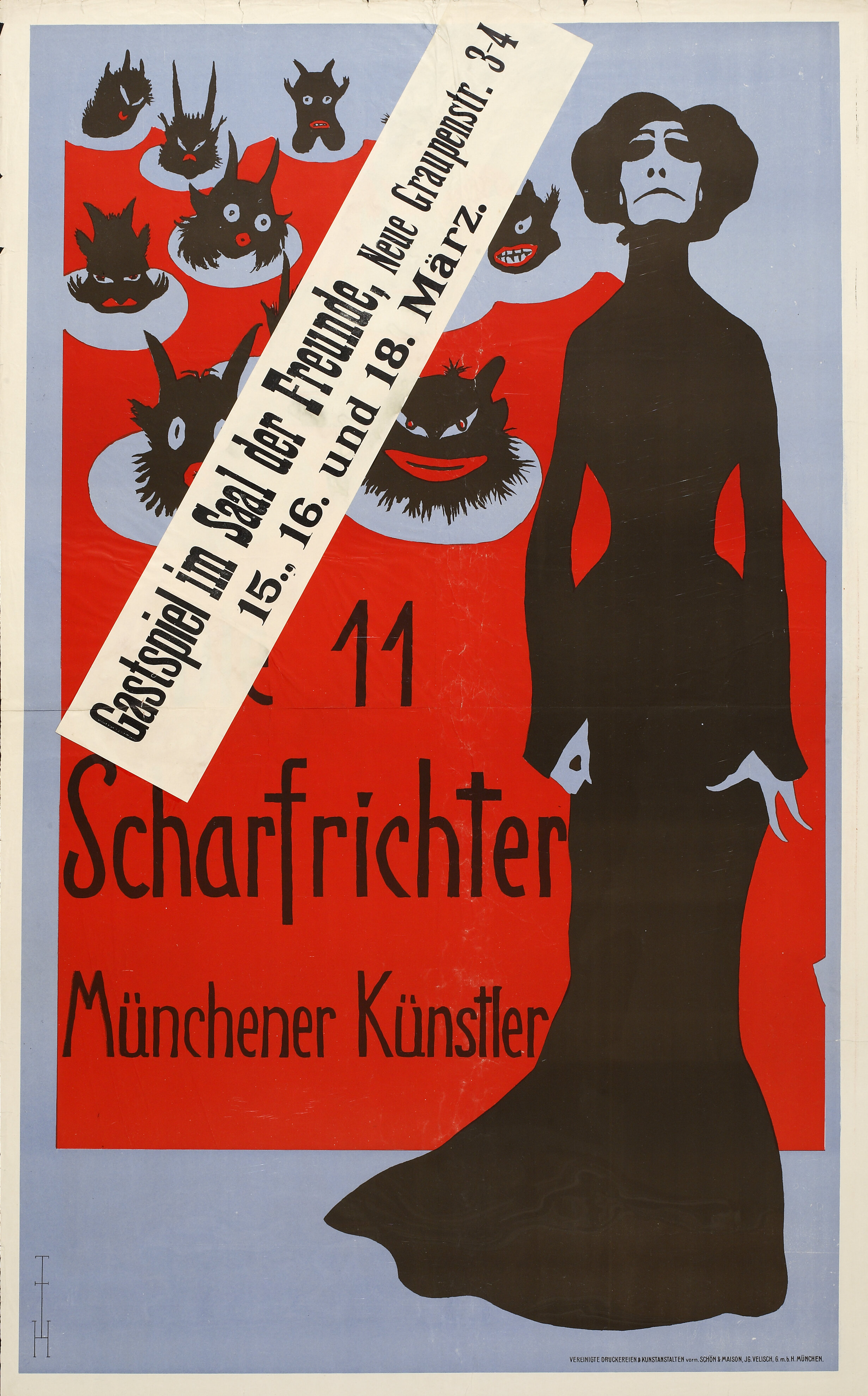

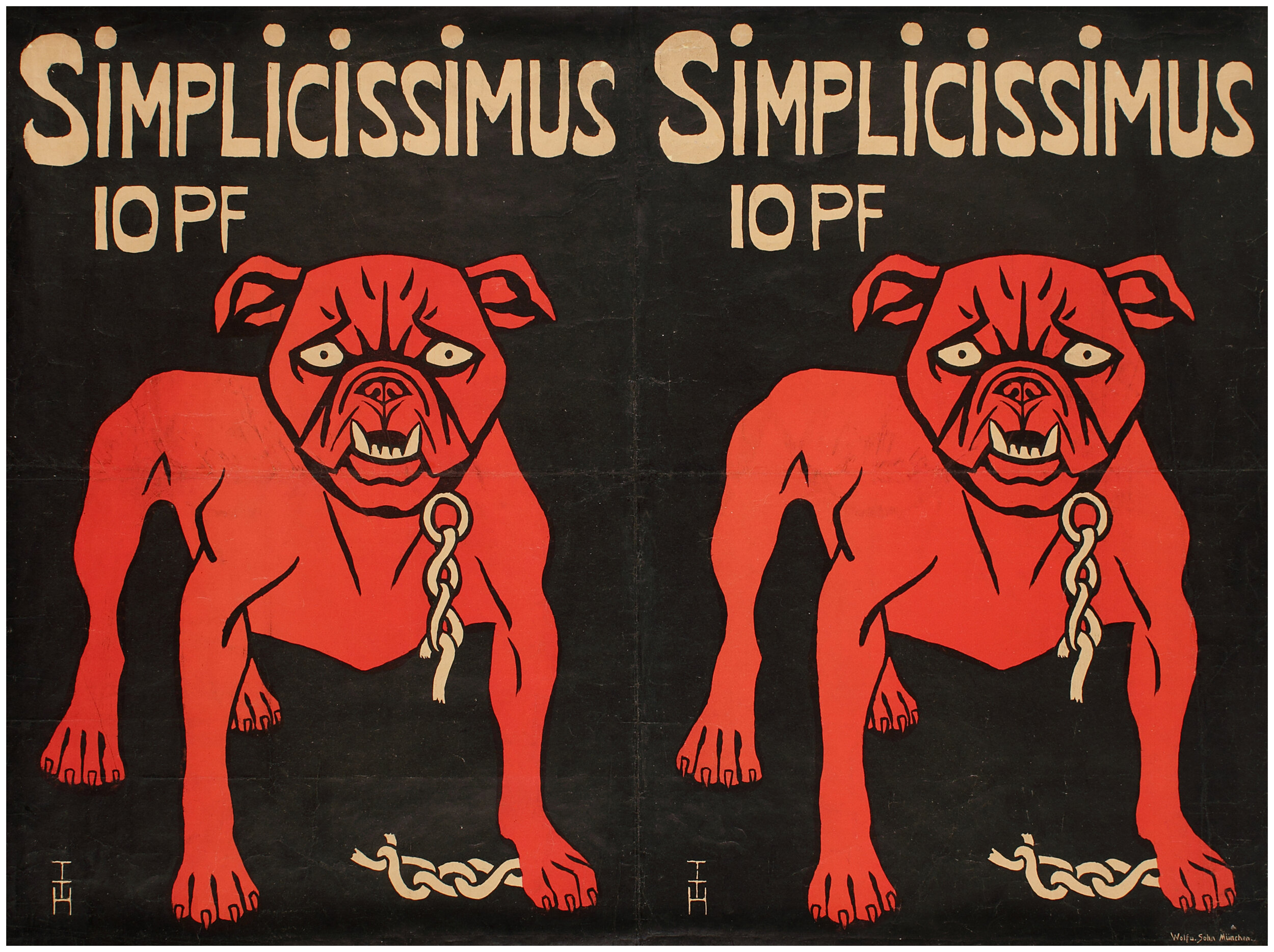

Jugendstil first appeared and flourished in Munich in the 1890s, an outgrowth of the recently unified nation’s desire to cement its identity through a cohesive style. Making no distinction between fine and applied arts, Jugendstil designers sought to reform everyday objects through a focus on function as well as form—though they also emphasized two-dimensional design. While it bears some superficial similarities to Art Nouveau, Jugendstil (which takes its name from the influential periodical Jugend) focuses more intently on figural art than does its more decorative French counterpart. Such figural work was on marvelous display in the pages of both Jugend and the more satirical weekly Simplicissimus. Thomas Theodor Heine and Bruno Paul were among the leading contributors to the latter; both artists also lent their designs to posters for the anti-authoritarian cabaret Die Elf Scharfrichter (The Eleven Executioners). In the end, though, Munich proved too conservative to sustain its artistic scene. Many of its key Jugendstil figures, among them Heine, Paul, and Ludwig Hohlwein, gradually dispersed.

Notable Artists

Thomas Theodor Heine

(Leipzig, 1867-Stockholm, 1948)

By the time he was seventeen, Thomas Theodor Heine was already turning heads with humorous drawings: his caricatures in the Leipziger Pikante Blätter earned him expulsion from school. Heine left his hometown of Leipzig to study painting at the Kunstakademie of Düsseldorf in 1884. From Düsseldorf he relocated to Munich, where he fell in with a group of painters that included a young Lovis Corinth, who greatly admired his abilities.

In addition to his painterly efforts, Heine contributed to the Munich magazines Fliegende Blätter and Jugend. Along with Albert Langen, in 1896 he was one of the founders of the satirical weekly magazine Simplicissimus, which criticized all facets of German daily life. Among Heine’s best-known images is the iconic Simplicissimus bulldog, whose broken chain and bared teeth exemplify the publication’s attitude toward authority.

In 1898, an issue of Simplicissimus mocking Kaiser Wilhelm’s trip to the Holy Land was confiscated. Heine, who had contributed offensive illustrations, and playwright Frank Wedekind, whose ballad “Palästinafahrt” alluded to the Kaiser’s delight in pageantry and self-promotion, were each charged with lèse majesté and imprisoned for six months. Langen, the publisher, spent five years in exile.

Although his chosen faith was Protestantism, Heine came from a Jewish family. After Hitler’s Sturm Abteilung raided the offices of Simplicissimus in 1933, Heine was compelled to flee Munich. Following stays in Prague and Oslo, he resettled in Stockholm, where he continued to produce paintings and caricatures until his death in 1948.

Bruno Paul

(Seifhennersdorf, 1874-Berlin, 1968)

With the blessing and support of his businessman father, Bruno Paul enrolled at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Dresden at the age of twelve. Paul chose to continue his studies at the Munich Academy in 1894, and soon enough his drawings were appearing in in Jugend. He joined the staff of the satirical weekly Simplicissimus in 1897, and until his departure from Munich to Berlin in 1906, he contributed some 500 drawings to the weekly’s pages.

Along with Peter Behrens, Richard Riemerschmied and others, in 1897 Paul was a founding member of Munich’s Vereinigte Werkstätten fur Kunst im Handwerk, which emphasized beauty and functionality in everyday objects. With this organization Paul developed furniture and interiors, including a Jugendstil Hunting Room that was awarded a grand prix at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle. Furnishings of Paul’s design received favorable attention farther from home, including at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. In 1907, Paul also helped to found the Deutsche Werkbund. That same year marked the beginning of Paul’s appointment as director of the school attached to the Berlin Kunstgewerbemuseum, a position he held until the Nazis forced him to resign in 1933.

Notable Posters

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster for Die Freistatt. 1904. Color lithograph on paper. 31 3/4" x 25 1/8" (80.6 x 63.8 cm). Printed by Oscar Consée, Munich.

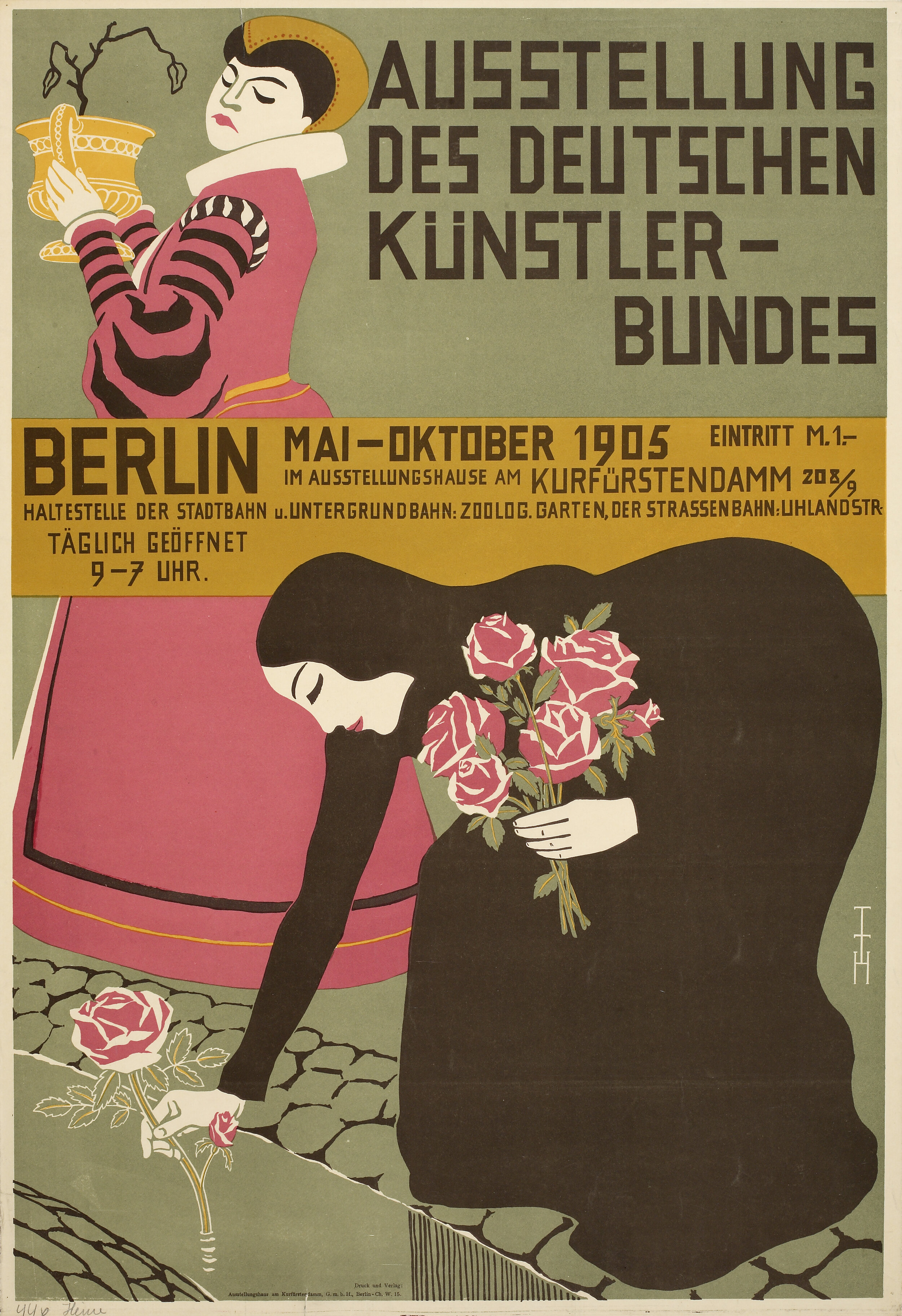

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster for an Exhibiton of the Deutschen Künstler-Bunde, Berlin. 1905. Color lithograph on paper. 27 1/4" x 18 5/8" (69.2 x 47.3 cm). Printed by the Ausstellungshaus am Kurfüstendamm, Berlin

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster for the Elf Scharfrichter, Munich. 1901. Color lithograph on paper. 44 7/8" x 27 7/8" (114 x 70.8 cm). Printed by the Vereinigte Druckereien & Kunstanstalten, Munich.

Bruno Paul: Poster for the Elf Scharfrichter, Munich. 1903. Color lithograph on paper. 45 1/8" x 27 1/4" (114.6 x 69.2 cm). Printed by the Vereinigte Druckereien & Kunstanstalten, München.

Bruno Paul: Poster for the Permanent Exhibition of the Vereinigten Werkstätten für. 1904. Color lithograph on paper. 25 3/8" x 16 7/8" (64.5 x 42.9 cm). Printed by Meisenbach Riffarth & Co., Munich.

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster for Simplicissimus. 1896. Color lithograph on paper, mounted on canvas. 29" x 38 1/4" (73.7 x 97.2 cm). Printed by Wolf & Sohn, Munich.

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster for the Fifteenth Exhibition of the Berlin Secession. 1908. Color lithograph on paper. 27 7/8" x 37 3/8" (70.8 x 94.9 cm). Printed by Hollerbaum & Schmidt, Berlin.